Slip-Sync System

JAMES CHADWICK’S SLIP-SYNC SYSTEM

Jim Chadwick adjusts the Pulse Camera as he prepares the Slip-Sync for a shake test. The rack of instruments, strobe heads, and Pulse Camera are early Chadwick-Helmuth products.

A theory of linguistics holds that language evolves to allow people to talk about what is important to them. If that’s the case, then SPIE founding member James Chadwick should congratulate himself. In the aerospace maintenance world, the phrase “chadwick your helicopter” is shorthand for the process of balancing the rotor blades of the aircraft.

“Chadwick” has become the industry term for the Vibrex™, a sophisticated camera system designed by Chadwick and his partner, Jim Helmuth, to monitor vibration and other periodic motion during this task.).

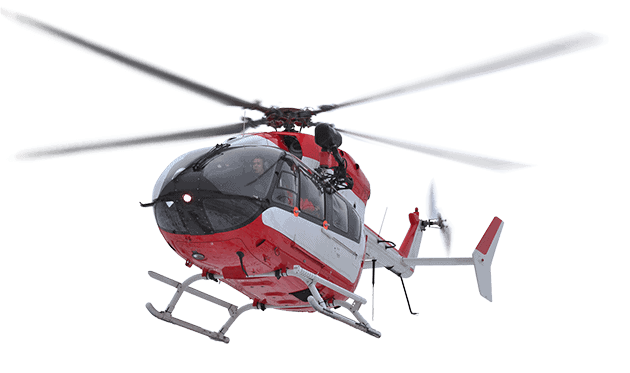

Slip-Sync technology evolved into many applications, including photography of human vocal cords and capillary blood flow, design of orange-grove antifrost-circulation fan blades (which eventually replaced the “smudge pots” of the early 1930s), and a complete system used to track and balance helicopter main blades and tail rotors. Balancing eventually extended to propeller blades, including the props on the world-circling Voyager. Vibrex™ systems are now the main product of Chadwick-Helmuth and are used worldwide.

Chadwick’s original design work was done in a small shop attached to the home he built more than 54 years ago in Bradbury, CA. The original Slip-Sync used an N-6 Gun Sight Aiming Point (GSAP) wing camera from World War II fighter planes. Converted into a pulse camera by Jack Urban, another early SPIE member, it eventually was replaced by a Bell and Howell DR70 spring-wound 16-mm camera, modified in Chadwick’s shop. A pulse camera capable of reliable operation up to 30 pulses per second was a breakthrough in the early 1950s. Chadwick’s Slip-Sync system was first used at the Jet Propulsion Lab (Pasadena, CA), documenting vibration tests of spacecraft components. It replaced the previous method—rolling a small barrel of instruments down the cement front steps of the lab.

As Chadwick traveled the world selling the Slip-Sync technology, he encountered customers who needed to balance helicopter tail rotors, which were failing because of excess vibration. The Slip-Sync system solved that problem, leading to a high-output strobe light, which could be used to track main rotor blades in the daylight. By the early 1970s, the Chadwick-Helmuth Vibrex™ became, and still is, the worldwide standard in the industry.

In the early 1930s, Chadwick inadvertently launched his career path at the age of nine when he asked his father for a telescope. His father responded, “Why don’t you build one?” He bought young Jim two glass blanks, which were once ship portholes. Chadwick spent almost three years hand-grinding the blanks and building the lens support tube and mount.

Finally, at age 11, he was able to look at the stars. He became the youngest member ever of the Los Angeles Amateur Astronomical Society. Chadwick realized, however, that he was a builder and not interested in astronomy as such; this interest was reinforced by his father, who gave him a lathe for his thirteenth birthday.

Chadwick’s interests expanded into photography and, in addition to taking pictures, he processed film and built enlargers. After two years at Cal Tech and a brief stint at Douglas Aircraft, he joined the Navy in World War II. His interest in flying literally was launched when, as a Navy officer, he was catapulted from a Navy Cruiser in a fabric-covered bi-plane on floats. His job was to take aerial photographs of the devastation of Hiroshima, Kobe, and Osaka.

Chadwick learned to fly in the late 1970s. Today he is still flying and taking aerial photos as he pilots his Mooney. Far from retirement, Chadwick is still at work, guiding his company through his son, Bill, who is also the company president. When not in the air, Chadwick is rebuilding classic Porsche automobiles. Chadwick’s original shop, attached house, and garage still exist; he lives next door in a new house on the same lot.